Living Well Into Advanced Age:

Daoist and Yangsheng Lessons Backed by Science

One of the enduring misunderstandings about ancient China is the idea that few people lived past middle age. In reality, while infant mortality lowered the “average” lifespan, adults who reached 30 often lived into their 70s and 80s. Historical records, medical texts, and village genealogies describe elders who practiced moderate routines—steady movement, simple meals, and daily breathing or meditation. These habits, rooted in Daoist and yangsheng teachings, offered a practical roadmap for longevity long before the language of modern science existed.

One of the enduring misunderstandings about ancient China is the idea that few people lived past middle age. In reality, while infant mortality lowered the “average” lifespan, adults who reached 30 often lived into their 70s and 80s. Historical records, medical texts, and village genealogies describe elders who practiced moderate routines—steady movement, simple meals, and daily breathing or meditation. These habits, rooted in Daoist and yangsheng teachings, offered a practical roadmap for longevity long before the language of modern science existed.

At the core of Daoist health cultivation is balance. Excess, whether in food, stress, work, or emotion, was seen as a source of premature aging. Many teachings emphasize eating “not too much and not too little,” favoring warm, digestible foods and seasonal variety. Today’s research mirrors this wisdom: moderate caloric intake, reduced ultra-processed foods, and diets rich in vegetables, whole grains, and plant proteins are consistently linked to lower inflammation and healthier aging. Scientists studying “Blue Zones” have arrived at nearly the same principles the Daoists described centuries ago.

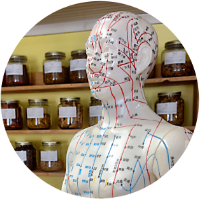

Movement was equally important. In Daoist villages and literati households alike, daily activities included walking, stretching, mild manual labor, or qigong-like movements. These weren’t workouts in the modern sense... they were gentle but regular. Contemporary studies show that even light physical activity, repeated throughout the day, improves cardiovascular health, preserves muscle mass, and supports cognition. Taiji and qigong, in particular, have been shown to enhance balance, mood, sleep, and immune function—exactly the benefits ancient practitioners described as “keeping the qi circulating.”

Breathing practices formed another pillar of elder vitality. Daoist texts encourage slow, quiet, abdominal breathing to calm the nervous system and support the body’s natural rhythms. Modern research into diaphragmatic breathing, vagus nerve stimulation, and mindfulness shows almost identical outcomes: lower stress hormones, improved digestive function, steadier heart rate variability, and better emotional regulation. In a world where chronic stress accelerates biological aging, these simple practices carry significant power.

So why did many Chinese elders historically live longer than people assume? Because daily life integrated these gentle habits. Meals were smaller, walking was built into the day, social connection was strong, and elders maintained meaningful roles in their families. These factors align with nearly every evidence-based model of healthy aging we have today.

Living well into advanced age isn’t about extreme regimens. It’s about rhythm. Moderate eating, steady movement, restorative breathing, regular sleep, and emotional calm, small choices repeated over years. Daoist and yangsheng traditions recognized this long ago, and modern science now helps explain why these practices work so well. Together, they offer a grounded and hopeful message: aging can be healthy, dignified, and deeply rewarding when we nourish life a little every day.

Links to other articles in this series:

- 1. Life and Ageing

- 2. How the Ancient Chinese Understood Aging

- 3. Wisdom Through the Decades

- 4. Living Well Into Advanced Age

- 5. Ancient Chinese Thought Maps to Modern Science