How the Ancient Chinese Understood Aging

(And What Modern Science Says Today)

When people imagine life in ancient China, they often assume most people rarely lived past their 40s. But historical records show something very different. Average lifespan was low largely because infant mortality was high. If someone reached adulthood, living into their 60s, and often 70s or 80s, was not unusual. Court records, medical texts, and ancestral genealogies all mention elders who remained active, taught younger generations, and practiced health-cultivation well into old age.

When people imagine life in ancient China, they often assume most people rarely lived past their 40s. But historical records show something very different. Average lifespan was low largely because infant mortality was high. If someone reached adulthood, living into their 60s, and often 70s or 80s, was not unusual. Court records, medical texts, and ancestral genealogies all mention elders who remained active, taught younger generations, and practiced health-cultivation well into old age.

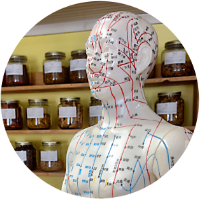

One of the most famous descriptions of aging appears in the Huangdi Neijing, a foundational text of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). It describes human development in a series of cycles: seven-year intervals for women and eight-year intervals for men. These weren’t meant as strict biological rules but as broad patterns describing how energy, fertility, strength, and vitality tend to unfold over time. Modern science has its own versions—childhood growth stages, hormonal maturation, peak adult strength in midlife, and gradual shifts in metabolism and muscle mass in later decades. Though the language differs, the idea is similar: our bodies evolve in predictable rhythms.

What makes the ancient Chinese approach notable is that aging itself was never viewed as a disease. It was seen as a natural expression of time, a process shaped by both inherent constitution and daily lifestyle. Rather than trying to avoid aging, people were encouraged to “age well” and to match their habits to each stage of life. The goal was not to stay young forever, but to maintain clarity, mobility, and inner balance as the years advanced.

In the Neijing’s view, the decline of Qi (vital energy), jing (essence), and blood over time is expected. But lifestyle could either slow or accelerate that decline. Moderate activity, good digestion, balanced emotions, and sufficient rest were considered essential. Excessive stress, overwork, irregular eating, or lack of movement were understood to wear down the body prematurely, ideas that modern research increasingly supports.

Today, scientists talk about “biological age,” inflammation, mitochondrial health, muscle preservation, sleep cycles, and metabolic fitness. Although the vocabulary has changed, these insights echo older principles: move gently and consistently, nourish your body, protect your energy instead of exhausting it, and cultivate a calm mind. Studies now show that taiji (tai chi), qigong, steady walking, a vegetable-rich diet, and restorative sleep all significantly influence how well we age, not just how long we live.

The ancient Chinese believed that aging well required cooperation with nature, not fighting it. Modern science increasingly agrees. While medicine provides tools for treating illness, daily yangsheng practices help maintain the foundation that keeps us resilient. Aging is not an enemy to defeat but a rhythm to understand. And with mindful habits, it can be a healthy, meaningful, and even graceful part of life.

Links to other articles in this series:

- 1. Life and Ageing

- 2. How the Ancient Chinese Understood Aging

- 3. Wisdom Through the Decades

- 4. Living Well Into Advanced Age

- 5. Ancient Chinese Thought Maps to Modern Science