What Does It Mean to Be Truly Calm?

In today’s world, we often hear about the benefits of being calm—reduced stress, better sleep, improved focus. But what do we really mean by “calm”? In the West, calm is typically defined as the absence of stress or anxiety. It’s a state we try to reach with techniques like deep breathing, mindfulness, or simply taking a vacation. Yet in traditional Chinese thought, calm is more than just a break from activities. It is a cultivated inner stillness, a central aspect of yangsheng, the art of nourishing life.

Stress is far more than a feeling—it’s a physical and mental burden. For instance, about 75% of Americans report experiencing at least one physical or psychological symptom of stress in the last month. Around one‑third describe their stress as “extreme,” and over 70% say stress affects their mental health. Chronic stress disrupts sleep in nearly half of adults, and around 43% notice physical health impacts, including headaches, hypertension, digestive issues, and lowered immunity. In a U.S. study, adults with high stress who believed it harmed their health had a 43% increased risk of premature death. Globally, approximately 38% of people reported feeling emotionally stressed “yesterday”—up from about 26% in 2007. These figures show how pervasive stress is, and why cultivating true calm matters.

Cultivating Calm in Daily Life

True calm doesn’t mean avoiding the world—it means engaging it with balance.

Simple Ways to Foster Calm:

1. Breathe with awareness: Take 3 slow, full breaths before answering a phone call or email. This simple pause helps reset your nervous system.

2. Move slowly on purpose: Whether making tea or walking to your car, slow down. Intentional movement cultivates inner quiet.

3. Create a calm corner: Designate a space in your home with natural light, minimal clutter, and perhaps a plant or incense. Use it daily, even briefly.

4. Align with nature: Observe the weather and seasons. Adjust your pace and meals accordingly. Nature is the original teacher of calm.

5. Practice letting go: Notice when tension rises—often it’s from trying to control what cannot be controlled. Exhale, soften the shoulders, and release.

As the Chinese proverb goes, “When the heart is at peace, the body is healthy.”

In Western psychology, calmness is seen as a temporary emotional state—one that can be disrupted by outside forces. Stress management aims to reduce arousal levels in the nervous system, using tools like meditation, exercise, or talk therapy. These approaches are valuable, but they tend to treat calm as a remedy for overload rather than a way of being. Even mindfulness, though now widely embraced, is routinely used as a tool to improve productivity or focus rather than as an end in itself.

By contrast, Daoist and Confucian traditions encourage calm as a foundational quality. It is not merely a reaction to chaos but a return to one’s natural rhythm. The Daodejing reminds us that “quietude” allows things to fall into place. Confucian teachings speak of cultivating a “still center” from which proper action arises. Calmness, in this view, is not passive—it’s a kind of strength, like a lake that reflects clearly because its waters are undisturbed.

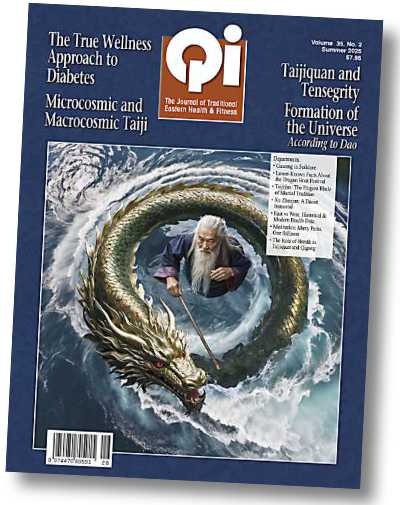

In the practice of Qigong or Taijiquan, "calm" is embodied. The breath is slow, the movements unhurried, and the mind is anchored in the present. One becomes aware of the subtle flow of Qi, and over time, this calm becomes portable. It follows the practitioner even into busy moments. This is very different from “relaxation” in the Western sense. It is not collapse or withdrawal... it is presence with ease.

So when we speak of calm in a lifestyle rooted in yangsheng, we are not only talking about stress reduction. We are referring to a kind of harmony between inner and outer worlds. To be calm is to live in accordance with the seasons, with one’s nature, and with the needs of the moment. It’s a quiet power—simple, stable, and profoundly healing.

Vocabulary Guide

- Yangsheng (养生): “Nourishing life,” a set of lifestyle practices aimed at promoting long-term health and harmony.

- Daodejing (道德经): A classic Daoist text attributed to Laozi, emphasizing natural order, stillness, and non-striving.

- Qigong (气功): An internal practice involving breath, movement, and intention to regulate and cultivate qi (vital energy).

- Taijiquan (太极拳): A Chinese martial art and health practice combining slow movements, balance, and mental focus.

- Qi (气): Vital energy or life force that flows through the body in traditional Chinese medicine and Daoist thought.