The Lost Human Posture:

Restoring the Deep Squat Safely (Part 2)

If the deep squat is a natural human posture rather than a fitness challenge, the path back to it should feel natural as well. We are not forcing the body to achieve a certain shape. We are inviting the joints and tissues to remember how to move. Each person begins from a different place depending on age, past injuries, daily habits, and basic anatomical differences. Some readers will reach the floor comfortably in a few weeks. Others may never fully settle into the posture, yet still gain benefits from partial depth. The goal is healthy movement, not perfection.

A helpful starting point is to notice how much movement is available before any strain appears. Stand with feet about shoulder-width apart and descend only until the heels want to lift or the knees feel pressured. Pause there and breathe. This position alone begins reawakening the ankles and hips that have adapted to chair height. Over time, that limit will lower. What matters is a steady, gentle approach.

A helpful starting point is to notice how much movement is available before any strain appears. Stand with feet about shoulder-width apart and descend only until the heels want to lift or the knees feel pressured. Pause there and breathe. This position alone begins reawakening the ankles and hips that have adapted to chair height. Over time, that limit will lower. What matters is a steady, gentle approach.

For many older adults, the ankles are the main restriction. Decades of shoes with stiff soles, limited walking on varied surfaces, and a lifetime of sitting reduce dorsiflexion. If the heels lift early, place a folded towel or a thin block under them. This is not a shortcut. It places the body in a position that allows movement to return, while ankle mobility progresses separately. Walking barefoot at home, slow calf stretches, and ankle circles all help prepare the range needed to eventually remove support.

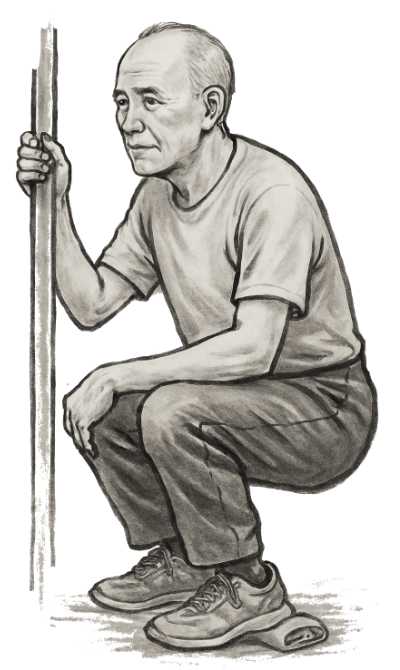

Balance is just as important as flexibility. Holding a countertop, door frame, or sturdy chair while descending allows the torso to stay upright rather than collapsing forward. A collapsed posture can strain the lower back and hips. An upright spine distributes weight through the legs more evenly and supports natural breathing. If a full descent feels unstable, try squatting toward a low stool, touching it lightly, and rising again. Gradually choose lower seats over time.

Knee comfort deserves special attention. The knees should point in the same general direction as the toes. If they cave inward, the hips and ankles may be asking for a slightly wider stance. Western pelvises often prefer a bit more turnout than those in many Asian populations. This variation is normal and does not violate the principles of the posture. Avoid forcing the knees toward an idealized photo. Follow what feels smooth and aligned.

People with joint replacements, arthritis, or long-term injuries may elect to keep the squat higher. A person with artificial hips, for example, may squat only halfway and still improve balance, core strength, and digestion. Someone with limited spinal mobility may focus more on posture and breath than on depth. Even sitting on a low bench with the feet wide and heels grounded can recreate some benefits. Progress always depends on personal history.

Throughout the practice, attention should remain soft. The breath stays relaxed. The body settles downward rather than bracing. The spine is long without stiffening. These qualities echo familiar principles from Taijiquan and Qigong. Mobility grows through mindful repetition, not force.

Once partial squatting becomes comfortable, the posture can be woven into daily life. Read emails from a low stance. Stretch your back in a squat while watering the garden. Pause in a squat while heating tea or waiting for a timer. Movement becomes part of living, not a separate workout.

Some will regain the full resting squat. Others will simply move closer to the floor than they have in years. Both outcomes are meaningful. Restoring the squat is not about turning back the clock. It is about returning to natural ways of moving that keep the body capable, independent, and grounded through the decades ahead.